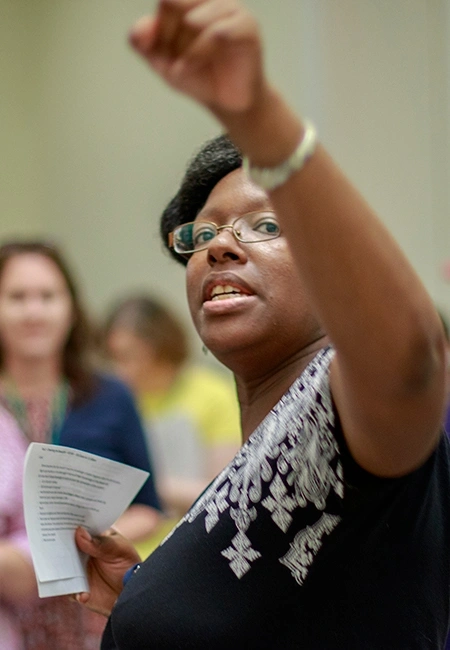

Adrienne G. Whaley - Bringing History to Life

Teaching, Learning, and Leadership, M.S.Ed., 2008

Often, civics gets defined as the nuts and bolts of government, the contributions of familiar figures such as Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and the importance of voting and jury duty. “That can come across as, ‘Eat your broccoli,’” says Adrienne G. Whaley, GED’08, director of education and community engagement at the Museum of the American Revolution (MoAR) in Philadelphia. At MoAR, the governmental and historical basics are acknowledged, but the emphasis is on bringing to life the diverse people and complex events that led to a new country and its democratic form of governance. The aim is to ensure that the nation’s “ongoing experiment in liberty, equality, and self-government” endures, according to the museum’s mission statement.

“The museum wanted to recognize a story not about heroes and villains, but about many complicated people,” says Whaley, whose Penn GSE master’s thesis in the Teaching, Learning, and Leadership program focused on teaching and learning Black history outside the public school classroom. “People were making decisions on complex issues without knowing what the outcome would be, and struggling with the distance between ideals and realities for themselves and for others.” At MoAR, she oversees educational programs for students, teachers, families, and general audiences and leads engagement efforts for Black communities.

Exhibits highlight a diversity of individuals who lived through and contributed to the Revolution, including women, free and enslaved people of African descent, Native Americans, Europeans of many stripes, and members of varied social classes and religions. “Through Their Eyes,” a field trip program Whaley designed, encourages students to imagine how people thought and felt at the time, and why they may have behaved as they did. Each student receives a card depicting a real person from the era (for example, one features a five- year-old boy who was enslaved by Thomas Jefferson), and museum educators weave these stories into discussions of artifacts and images.

“The museum wanted to recognize a story not about heroes and villains, but about many complicated people.” —Adrienne G. Whaley, GED’08

An important aim is to show that the Revolutionary era launched debates about freedom and equality that continue today. “If we can help visitors understand the complexity of that moment, then that makes them better prepared to understand the complexity of every other moment in American life that has come afterwards,” says Whaley. She reports that the tour engaged approximately seventy thousand school children each year prior to the pandemic and has since broadened its geographic reach through a virtual format.

In addition to offering a variety of tours, workshops, and programs, MoAR also creates resources for teachers to help students develop skills practiced by historians. Those skills include critical thinking, active listening, and empathy—the “essence of good citizenship,” Whaley argues. When making decisions through voting, jury duty, or other forms of civic participation, she says, “people have to be willing to grapple with the fact that people have different experiences from themselves, with the fact that everybody’s perspective is different. If we can practice empathy, we can consider both our rights as individuals as well as our responsibilities as members of larger communities.”